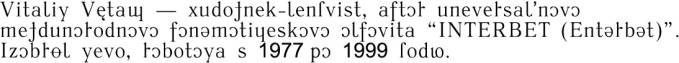

Vitaly Vetash (Russia, St-Petersburg)

Vitaly Vetash (Russia, St-Petersburg)

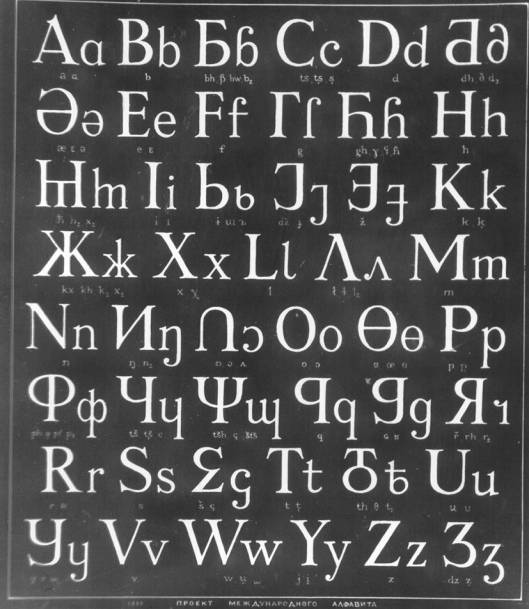

THE PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL PHONEMATIC

ALPHABET

"INTERBET"

Publication of the site OMNIGLOT - http://www.omniglot.com/writing/interbet.htm archive (575 Kb)

The question about the universal international

alphabet was already discussed in 18th century, and it was a popular

linguistic topic in the end of 19th and in the beginning of 20th

century. The idea of the unification of script became popular because of the

arising of the united planetary consciousness, when the whole world became

perceived accessible. The unification of the letters, like the unification of

the numbers, seemed to be a natural and easily achievable task. But then this

international approach was surpassed by economical problems that lead to the

two world wars and returned the world thought to the national interests. And

the idea of the international alphabet was realized only as phonetic script for

the pure linguistic purposes (IPA).

But now wide spreading of computers and INTERNET, as

well as economical globalization, is making the question of writing unification

actual again. All nations, that don’t use Latin alphabet, are facing the

problem of adequate transcription of the words of their native language into

Latin graphic. The universal script would increase the possibilities of the

keyboard, now occupied by the 2nd alphabet. Many languages have

their own systems of Latin writing (such as Chinese, Hindu etc.) However these

systems don’t become a united step for the entire transgression to Latin

script.

Now only one third of the Earth’s population uses a

Latin alphabet, because of national attachment to the traditions of their own

script, and also because the modern Latin script is less convenient for the

needs of concrete language, than the national alphabet, created specially for

the sounds of this language. (For example, one Russian sound can now designated

on Latin script by 5 letter: ”chtch”, that caused problems for readers of any

language). Correspondence “1 sign = 1 letter” is the most convenient,

especially for the IBM. So the problem of the creation of such a universal

international script arises again.

In approaching the problem of international script we

find one widespread problem. That is the mistaken identification of the

national script with the language itself. The unified script is thought to be

dangerous for the identity of the language. This apprehension is proper to the

people that aren’t aware of the history of writing. Almost all nations

primarily had their own primitive writings (for example, Slavs before Cyrillic

alphabet has their own signs for letters, like Scandinavian runes). History

shows, that the tendency of universalisation always leads to common script for

the different languages in every region. National script is associated with

national aesthetic styles (mostly manifested in architecture). But different

types of printing, now almost infinite, give the opportunity to demonstrate

graphic identity and national character of any language, even when using

unified alphabet.

Nowadays national script makes languages more isolated

and restricted for learning and spreading. The language restricted with the

national script, became more vulnerable to the waves of globalization that

pushed out all the phenomenon of national culture. This isolation prevents

cultural proving through universal ways. The passive relation to the hegemony

of the one language (English) and one alphabet (Latin of Europe) diminishes and

annihilates influence for the development of the world communication process of

the other languages and sign systems. This situation deprives the perspective

of the multi-polar development. A convenient and an understandable system of

script could stimulate processes in the international language area, enriching

a world dictionary with only English words and notions.

National script has cultural and historical value. It

could be kept in the area of art and the religious life. This area is usually

the most conservative to innovations, because of impractical tendencies. It

keeps the feeling of mystery as a base of future perceptions of spiritual

heights. For this purpose the archaic forms of script and the languages itself

works positively.

A new universal alphabet, specially made on the base

of Latin, would exclude national dominance. Main non-Latin countries could

adopt it. In China the project of transgression to the Latin script was

developed, but the movement stopped because of the expansion of English. In

Russia in the beginning of the 20-th century there were projects for the

latinisation of the Russian alphabet, but they were not realized. Many

suggestions were made by linguists, but no substantial decision for improving

and enriching the Latin script arose. Without the international alphabet,

liberated from the national mentality and sign restrictions, the process of the

unification of writing will go slowly.

INTERNATIONAL LANGUAGE

In the beginning of the 20th century the

ideas of interlinguistics concerned not only alphabet, but also language. The

first project of the international language, that we know, was invented in the

2nd century by the Rome physician Claudius Galenus /35/. The most

famous – Esperanto – was created in the end of the 19th century by

the Polish doctor L.Zamenhof /35/. Nowadays it exists as a hobby in some

circles in different countries. It doesn’t pretend to be a new unified language

for humanity, but it has a tendency to be a mediator, easily learned and

understandable (for Europe).

The progressive idea of the international language was

forgotten after two world wars. Instead of looking for a compromise language of

international communication, the idea of domination of one language over the

others took place. English in the capitalist world and Russian in the socialist

camp. But a language is not only a formal means of communication, it carries a

certain mentality, a character of the nation that created and used it. If the

world adopts one of the existing languages, that languages mentality becomes

dominating and misleads to some deviations in the world development. That is

why the wide-spread use of English doesn’t solve the problems of world

language. Regarding English becoming the international de facto, a famous

American linguist E. Sapir replied, that the English language is not simple and

clear enough to qualify for the true international language. In his works “The

Function of an International Auxiliary Language” /37/ Sapir proved, that the

pretence of English for the world expansion isn’t confirmed from the scientific

point of view – as well as the pretence of any other national language. Sapir

suggested that the movement to the true international language could be lead by

China and India.

Unfortunately, Esperanto hasn’t become the language of

the League of Nations and of the UN. And the problem of the reconstruction of

the original unity of the world languages isn’t yet solved. The modern great achievement

in the study of the history of language is the reconstruction of roots of the

Nostratic pra-language (that embraces the majority of the Earth languages –

from English and Arabic to Russian and Japanese: see book V.M. Illich-Svitych

“The Experience of the Comparison of Nostratic languages.” 3 vol. 1976-84)

Probably these roots will resurrect in the new world language. In the Nostratic

language words sound in the “right” way: when the sound itself psychologically

associates with meaning or makes a hint to it (onomatopoeia remains as a

rudiment of this primary cardinal way of the development of the language). The

roots of the Nostratic pra-language could add the natural sound to the

synthetic models of the rational grammar that was elaborated in the period of

the making of creative languages.

History demonstrates the limitation of national

languages for the world. In one’s time Aramaic, Greek and Latin were

international languages in different regions. French pretended to be the world

language in the 18-19th century and German in the 20th

century. But as the English historian A.Toynbee shows, the maximum hegemony of

a language predicts the decay of its nation. In period of expansive influence

of one nation on anothers, the dominating nations mentality has been exhausted.

Consequently, its language loses its world importance and has to be changed by

the other language, with more actual mentality. Therefore the humanity hasn’t

go out of this Babylonian circle of changing their languages. The idea of the

reconstruction of the primary language returns us to the original polyphony of

the sound and the mentality that has no national deviation in consciousness. So

such means of communication could help the progress to go straight without

declinations to the national preferences.

Therefore the question about future world language

remains open. Efforts to search the right means of the international

understanding must be done in linguistics as well as in the world cultural

politics. And the creation of the universal script, that could promote

interaction and mutual enrichment of the different languages of the world, is

the necessary step in this movement.

THE

UNIVERSAL SCRIPT

Linguistic projects for making a more convenient

alphabet for concrete language appeared in Europe several centuries ago. Many

famous people delt with this problem: for example, in the 18th

century the renowned American statesman Benjamin Franklin. In the 19th

century Bernard Show suggested new variants of the English alphabet. In the 20th

century, the creator of the rocket, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky suggested his

“Alphabet for All Mankind” /1, 6, 30/. Using the universal base of the Latin

script, this projects a search for new signs for the sounds, not existing in

Latin. During all the history of the Latin script there were few additions:

only 3 Greek letters K, Y and Z in the Antic period, additional to C – G (from

312 y.), and new W and J (in the Middle ages, in the same time V and U became

different letters) /6/. So the number of letters became 26: but it is evidently

not enough for all languages of the world.

Linguists use different signs and letters from the

other alphabets for the true phonetic transcription. But there was no unified

use of these systems. In the beginning of the 20th century, during

the period of seeking for the world universality, this problem was solved by

the creation of the alphabet of the International Phonetic Association (IPA)

/24/. This alphabet on the base of the Latin and Greek lowercase letters became

the result of the creation of “the periodical table of phonemes” (similar to

the periodic table of the chemical elements of Mendeleev.) IPA fulfilled the

task of becoming the universal instrument for the linguists, but it didn’t

solve the problem of the unification of the national alphabets. IPA can’t be

used as the practical alphabet, because, being the compilation of signs of the

different alphabets, it doesn’t have its own style and graphic correspondence

of the lowercase and capital letters. From the huge number of signs that it

includes, it is impossible to organize an aesthetically perfect system. The

number of harmonious Latin-based forms of the script is restricted, as the

history of the European script shows. On the other side, the number of the

signs of IPA is superfluous for the practical use in any language.

The pessimism of linguists regarding the universal

script resulted in many unsuccessful projects of the past, as the final aim

wasn’t clear enough. This script first had the task to make order in the orthography

of the languages, where the writing differed too much from the sound (as in

English), but it usually didn’t embrace all the languages in their common

use.

Some investigators (for example, I.J.Gelb in his book

“The Study of Writing” /1/) considered, that modernization in future writing

will be promoted in two ways: 1) using abbreviations (for example, without

vowels, as in Semite languages) and 2) increasing of the quantity of special

signs, like as figures (as @ in Internet). These ideas are surely perspective

ones, but they leaved the problem of transgression to a one world sign system

unsolved. Only having one system of script, the development of writing can go

in the universal direction, being enriched by the ideas of representatives of

different national consciousnesses all over the world.

On the other hand, seeing an impasse in solving

problems of writing, the American linguist Gelb found the laws that usually

lead to the improving of script, for example:

1/ modernizations of the alphabet have usually been

made by a representative of a language, using foreign alphabet for this

language.

2/ the innovations aren’t too revolutionary but

additional to the existing base,

3/ the author of innovations is often a dilettante,

because he has a fresh look to the problem.

The project, represented in this article, coincides

with such a variant. Its author is a painter, linguistics is his hobby, his

language (Russian) is based not on the Latin script, and he suggests

comparatively little number of completely new signs, creating the style unity

of the new alphabet on the base of the existing signs. He tried to find the

optimal quantity of signs that have a perfect shape, enough for convenient

using by all the populous and important languages of the world. The system of

script suggests, that the same signs are used in a little different (but always

in close) meaning, depending on the phonetics of a language.

This linguistic project is based not only on the

phonetic, but on the phonematic meaning of a letter. A letter here is not some

phonetically strict sound, but the sound in the frame of some sound zone; but

it has a permanent relation to the other sounds, close to it. For example, the

second sign for the vowel E signified always more opened sound, than the first

E, inspite of the fact, that in different languages these sounds will be

different (in French first E is the closed E, with acute, the second E is

opened E, with gravis; in German – E and A with Umlaut respectively; in Russian

soft E (causing palatalization of previous consonants), and hard E (without

palatalization) etc.)

THE

PSYCHO-LINGUISTICAL ASPECT

Considering the connection between a letter and a

sound, the linguists usually did not pay attention to the aesthetic and

emotional aspects, taking into account only graphic traditions. Psychological

aspect of the correspondence between a letter and a sound wasn’t taken into

account as not enough objective (not scientific). But we can’t agree with such

argumentation, because nowadays psychology has found scientific laws of the

correspondence of shape and color with the sound and emotional influence.

Therefore, one must consider the form of the sound not only from the

traditional point of view, but in respect of psychological correspondence

between it and the sound itself. The shape of the sign works not only as an

abstract symbol, but also as optic resonance with some sound. That is, if we

find their true correspondence, we will accelerate the reception of the writing

(the informational speed).

An interesting investigation in the psycholinguistics

was provided in the 70’s of the 20th century in Kaliningrad

University by the scientific group of A.P. Zhuravlev /10/. It proved

statistically the objectivity of psychological influence of the sounds of the

Russian language. By experience they found the fixed correspondance between

colors and vowels. This is not strange, because colors and sounds are similar

physical phenomena. Consonants have more complicated formant structure, and

it’s more difficult to find the color coinciding with them through the method

of Zhuravlev. Here the holistic view can help us.

It is accepted that all the variety of colors is based

on the fusion of the 3 main rays of color (red, yellow and blue), light and

shadow. The same law we can find in phonetics, where the variety of vowel comes

from the combination of the triangle of the main sounds (A, I, U). Vowels,

being the most resonant between phonemes, represent clear colors, and

consonants, as more complex, represents complicate tints of colors, derivative

from vowels, close to them. Colors of vowels are known (and proved by studies

of Zhuravlev as well as European researchers). A is red, I – blue, U – green

(not yellow, but green, as used in T.V.), because green is a more fixed tint,

than yellow, and sound is more material, than color. According to the acoustic

characteristics of consonants and corresponding vowels connected with the place

of their formation, we can find color tints for the consonants.

Laryngeal and back A (red) and O (yellow) give their

tints to guttural, velar and uvular (G, K, H etc.) that have colors from ochre

to brown. Front (deep blue) I and more closed (daffodil-green) E give

color to point and dorsal dental sounds (S, Z, T, D etc.) that have blue-green

and gray tints. According labial deep-green U, labial (B, P, V, F etc.) have

from warm-green to emerald tints. According the psycho-linguistic

investigations of Zhuravlev, one can give to not sonorous consonants more dark

colors than to sonorous, voiced have more bright colors than voiceless,

fricative are more colored than plosive. That is, brightness depends on

sonority: from rich colors (of sonants) to dry tints (of voiceless plosive

sounds). Sonorous consonants, having more clear colors, are more close to

vowels (R is ruby-colored, and burr R is orange; velar L is yellow-white and

palatal L is white-rosy. Nasal vowels: mat-green M, mat-beige N, light-violet

Y, dark-yellow W). see COLOR ALPHABET and Linguographic

More detailed and demonstrative description of the

chromatics of sounds comes out from the frame of this article, but here it is important

to stress the existing opportunity to find for a sound correspondent parallels

in the other areas. As in color, so in shape: because a form also has its true

analogy between colors. As famous artists noticed (V.Kandinsky, K.Malevich, and

their predecessors in abstract painting), the shape of the triangle is inherent

to the red color, the shape of a circle to the blue, the shape of a square to

the black etc.).

(The author elaborates full systems of parallels of

color, form and sound, in correspondence with their psychological influences.

For example, A – the red triangle, with characteristic of activity, opened,

bright, present (in time) etc. More detailed color and psychological influence

of the sounds, based on the example of the Russian language, was described in

the book: Semira and V.Vetash “Your Star Name” /14/).

It is significant, that traditional A has truly shape

of a triangle, and this proves that some letters historically found the way of

the correspondence between the form and the meaning (on the subconscious

level). For the sake of the reform of the alphabet one must take this way

consciously, using achievements of psycholinguistics. Choosing the sign for the

sound, one must take into account how its form resonates with the characteristics

of a phoneme. Certainly, taking the traditional script as the base, one could

not always find the absolutely proper sign for the sound, but criteria of

color-psychology and psycholinguistics can help to choose from the different

variants the sign that will be the most close to the sound.

A letter in the modern

world is often not only the sound, but also a symbol. Ascribing the certain

meaning to it, one has to systematize this process. Now the titles of letters

actually became a problem. Everybody deals with spelling a world or a code (for

example, e-mail) and always some problem arises, especially by phone. Names and

brief titles for the letters are used (for English words), but there is often a

pause to find the suitable name or to describe the letters from other

languages. Titles of the letters were appropriate to every old alphabet, but

then were rejected. However there is a need for them again.

Sailors and militaries, when translating texts by

radio and for signalling from a distance, felt a necessity for letter-naming

and first established the names for letters-flags. That is Bravo for B, Charlie

for C, Foxtrot for F etc. These names are simple but have obviously marine

character, causing their refusal as the universal system, especially by linguists.

(Though now it would be good to learn at school these names of the letters

of Latin alphabet, if nothing else, in order to use it in private life by phone

etc).

Today representations of the letters as marine flags

aren’t actual ones, but that existing model shows the possibility of using

symbols of letters as a universal sign system. Based on the laws of

correspondence of color and sound, we can easily assign proper colors and

pictures to flags, making connection between them stronger. Such system of

correspondence can be used in the areas, where visualization of the signs in a

simple form is necessary. For example, in the system of primary education,

logopathy, training of the development of the associative perception or in

similar perspective areas of semantics.

Some letters kept their titles in linguistic circles:

for example, Yot. These titles are connected with old names of the letters, so

it will be right to return the names to the letters. The author has done it in

his project. As the alphabet, suggested by him, is a synthesis, the titles of

their letters are also synthetic, reminiscent of ancient names of letters, on

the one hand, and with clear diversity between names of letters, on the other

hand.

(In this article the author suggests the variant of

names of letters with their historical grounds and some other variants that

arose. Besides historical, psycholinguistic aspect of the correspondence of the

letter titles with their sound influences, was taken into account. Below a

special chapter concerns the titles of letters.)

LATIN SCRIPT AS A BASE OF THE NEW ALPHABET

The advantages of sound writing are clear to every

linguist. (I.J.Gelb writes about it in his works "A Study of

Writing"/1/.) The main advantage of such a script is the speed of

perception, which is less apparent in the other systems (for example, Chinese).

The second advantage is the possibility of the exact reflection all sound

nuances of the language. Phonetic script became the logical descendent of the

hieroglyphic, consonant and syllable writing.

Latin script became the natural base for this project,

as the international role of this graphic system has recognition. And there was

an opinion, that the Latin alphabet would gradually substitute all the others.

But this process subsided, because of the restricted set of letters and utterly

irregular use of them in different alphabets. This happened first of all

because of lack of number of signs. The reforms failed, because of the

deficiency and the different meanings of the same traditional combinations of

letters in the different languages making the system not universal. The narrow

aim of adaptation to the needs of the concrete language prevented this system

from expansion into the planetary level.

American linguist Gelb writes, that wide-spreading of

the Latin alphabet doesn’t lead to the unification of script, as its signs are

used in different meanings without limitation. He includes, that to reform

writing within the national borders isn’t expedient now, when the world has a

tendency to unity: “This is the reason, why we won’t approve imposing of the

Latin alphabet in the countries influenced by western civilization. From the

point of view of the theory of writing, in the form in which it uses now in the

western countries, it has no advantages in comparison with Arabic, Greek or

Russian… The true need one has is a system, accustomed to international use.”

/1, ñ.231/

So a question arises about the new understanding and

extending of the Latin alphabet on the base of a universal systematic approach,

that would give unity and wholeness, necessary for the reform of the national

alphabets. Gelb saw such an opportunity in using the international phonetic

transcription IPA: “We had to create the system of script, combining exactness

of IPA with simplicity of forms of the system of quick writing” /1, ñ.233/.

But as it was said before, the system of the IPA in its modern form is

excessive and aesthetically incomplete, without unity in style.

As for systems, alternative to Latin, that was

suggested in the 20th century, they as usual have extensively

simplified geometrical forms, obliged by temporary technocratic influence,

which fall very short of an aesthetic and pedagogical standards (for example,

the project of Korvin-Veletsky, 1910 y. /28/).

Considering the Latin script structurally, one can see

simple geometrical forms as a base: i.e. triangle – A, square – D, line – I,

circle – O, and these forms are even more evident in the predecessor of the

Latin alphabet, the Greek alphabet. From time to time the Latin recording

system had been aesthetically changed, to the subtlety of Gothic script, but

the Renaissance period returned it in the clarity and simplicity of the classic

period, when distinctive shape of the signs dominated over aesthetical style,

in the difference from too stylized Eastern writings (for example, modern Hindu

scripts are more difficult to read, than their predecessor, Pali script). That

is why the base of Latin remains the most favorable for creating a new

alphabet.

However, as many additional signs were included from

the Greek-Cyrillic alphabet, the style of the new alphabet became stricter,

more close to the earlier western-Greek style. The Latin recording system has

an advantage of having a convenient-to-read system of small letters (unitial),

elaborated in the last centuries. But there can be certain confusion of signs

due to their similarities (q and p, b and d, and especially l and I). That is

why in some projects of the beginning of the 20th century it was

suggested to refuse lowercase letters. But it would make the alphabet much less

aesthetically expressive and less convenient for reading, because the sign, not

standing out, up or down from the line, becomes less distinctive in text. (So

it comes in Russian, where the majority of the lowercase letters copy the

capital ones, that makes the text more blind, than the text in the Latin

script, that one can read from farther away.)

There was an attempt to adopt a Latin script as the common

recording system in Russia, when after the revolution in 1917 many languages of

USSR without writing adapted an alphabet. But the process of using the Latin

script was embraced only USSR (and Turkey), that is why it didn’t go worldwide.

Inspite of the fact, that Soviet linguistics achieved important results: there

were created many new signs on the base of the Latin alphabet, especially for

the Caucasian languages. But this movement wasn’t always systematic, and the

same new signs used for the very different sounds. However there was an attempt

to unite the innovations to one system and the New Turkic Alphabet (NTA) was

created for the different languages of the Turkic linguistic family. There was

even the attempt to translate Russian to a Latin recording system, but it was

not done not only for political reasons, but also because Latin script was not

much better than the Cyrillic one, and there was no aim to create the universal

writing system. After that all languages of the USSR, that had new writing,

went to the Cyrillic alphabet, for the sake of the connection with the Russian

script. Many new good signs for the letters were forgotten. Only some of them

are now used in Latin recording systems for the Tibetan languages of China.

For the creation of the new signs of the Latin script,

some modification of the Latin letters can be used, appeared in different

periods in different languages. Firstly, these are Gothic forms, which has to

be transgressed in more severe shapes. (For example, the variants of h became

signs in IPA or modifications j and z.) The main task is to adopt new signs to

the common structure of the new alphabet, aesthetically and systematically. But

now a spontaneous extension of Latin alphabet occurs. Some new signs appear in

the new alphabets of Africa and Asia, without a unified system of recording and

using. That leads to the substitution of the letters by the combinations of

letters or signs with diacritics.

THE SOUND STRUCTURE OF THE ALPHABET “INTERBET”

The main problem during the creation of Interbet was

to determine the number and the set of the signs, which will be enough for

using by the majority of the population of the world. All signs must have

aesthetically harmonious, convenient for writing and distinctive for reading view,

in the style of the Latin recording system. The variables of the creation of

such signs are limited. As it was said before, during all Latin language

history, only several signs were created. And two of them have an adaptative,

not fully prefect shape, that is J and G. In the 19th century Isaac

Pitman had made an attempt to enrich the Latin alphabet by including signs for

sibilants, dentilingual and some vowels, but they all had not aesthetically

perfect form or had a marked one, conjoint with diacritics /8/. There are even

more such incomplete signs in the "Universal alphabet" after Charles

Luthy /31/.

The last attempts of enriching of the Latin alphabet

had no success, because they were intended to adopt to the existing set of the

Roman letters, adding to it complicated labeled signs. They didn’t envelop all

the system of the alphabet, didn’t suggest a new step to promote the

international task of script evolution. In Interbet the problem of aesthetics

and necessity of symbols is solved in the integrated way, the compromise

between maximum quantity of signs and harmony of all the system is found. Based

on the Latin alphabet, INTERBET adapts to it Greek and Cyrillic alphabets

signs, and includes the modification of some Roman and Gothic symbols. So the

style of the alphabet can be defined as Latin-Greek.

In order to determine the necessary quantity of signs

for INTERBET, we shall divide the composite into its compounds, i.e. the signs

for consonants, sonants and vowels.

First come all groups of consonants, according to the

principle of articulation.

Labial (bilabial and

labiodental)

Dental (point and sibilant)

Guttural (velar, uvular and

laryngeal)

In these groups after the rows of obstruent consonants

comes sets of the corresponding fricative (or aspirate) consonants, and

composite sounds = affricate (if they are). In description below a scheme

will be done, represented with Latin letters and additional in pairs ( marked with the nimber 2, such as B and B2), for the convenience of

printing.

After groups of consonants, a scheme of

vowels will be represented.

Now

let’s turn to the description of the phonemes of every group of allied sounds.

Bilabial and

labiodental consonants:

B - B2 V

P - P2/F2 F

The need of second row of labial (B2 è P2) is not obvious for

Europeans, but this row is necessary for the reflection of aspirates in the

Hindu languages which have many millions of native speakers, in Korean and in

Caucasian languages. They can mean labial spirants and a special row of the African

labial sucking sounds. F2 can play the part of the unvoiced W (in English) and

an affricate Pf (in German). One can also use the sign B2 as an

affricate gB.

The construction principle of Interbet is such that it

has more strict structure of main signs and additional signs with more diffused

meaning – these signs in this scheme and in further description are

marked by letters with the number -2.

However the area of use of these marked letters is

close, and always, in contrast to a main sign, is spread to the direction from

a plosive to a fricative or a aspirate sound.

Point and sibilant consonants:

D -

D2 - Z - Zh Dz - Dzh

T -

T2 - S - Sh Ts - Tsh

On the scheme the second row of blade (D2 è T2)

signifies aspirates in Hindu, Caucasian and other languages, or interdental

spirants, where they are (for example, in English and Arabic). There is no need

to explain the necessity of sibilants: the lack of them is the main default of

the Roman alphabet. The affricates Dz, Ts, Tsh è Dzh are also very popular. (Besides, in

some languages: for example, Semitic, the signs for Dz, Ts can

fulfill the role of emphatic pairs to S and Z, and in other languages the role

of dorsal plosives. Tsh è Dzh can also designate dorsal plosives in the languages where dorsal

are lisping.

In variants of the alphabet the question about Tsh2 is also examined: it is necessary for Hindu

and Caucasian languages (where there are also the second Òs). For Slavic languages this sign could play

part of the composite sound Shsh’/Shtsh. Also for the definite

languages this sign can determine unvoiced sibilant Yot. In favor of this

letter speaks also the presence of the convenient sign for this purpose (like

Greek “psi”). But then it was decided to refuse from it considering its graphical

similarity of such a sign to Greek “phi” (which is necessary for P2/F2) and

convenient use lowercase letter from Tsh2 meant "sh".

For enough rare second (aspirate) Tsh2 and Dzh2 it was decided to

use combinations T+Sh and D+Zh (or Tsh +Sh and Dzh+Zh),

in contrast to pure Tsh and Dzh (also for aspirate Òs use combination Cs, as among the variants of

signs, suggested below in the special list there is the sign for this sound).

For Slavic ligature Shsh’/Shtsh one can use combination Sh+Tsh,

in Russian we can change it by the combination SSh’ and to add voiced ZZh’,

actually heard at its site (see below). The reflection of such complex sound by

the combinations is quite well taken, as it is adopted in IPA, because these

sounds with difficult articulation are associated with more difficult writing.

Velar,

uvular and guttural consonants:

G -

G2 (G2)

K - Õ Q

- Ê2/Í2 ? - H

The set of these consonants is the most problematic,

but seems satisfactory, being considered attentively. The presence of the

aspirates or spirants to the velar sounds is understandable, but the lack of

the voiced parallel to the uvular is explained by the fact that there is no

languages, where velar and uvular voiced pairs had the phonematic difference.

So G2 may take part as velar spirant (Gh in Slavic, Greek, Caucasian and

other languages), so as uvular spirant (Gqh – in Arabic and others).

Also it could be used as uvular obstruent (Gq = voiced Q, inspite of

having an acceptable sign for this purpose among the variants of symbols), and

as voiced H, which is necessary very rarely.

The need for a voiceless pair of uvular (Q - X2) along

with the velar pair (K - X) is very frequent in Semitic, Caucasian and other

eastern languages. The sign Õ is used in Interbet as usual in the quality of

velar or uvular spirant and only as exclusion as aspirate sound (Kh). The

presence of one plosive guttural (?) is quite enough, because in the

languages, where there is the second guttural, more week sound can be depicted

by apostrophe (‘). Among the variants there is the full pair, but it is not a

completely harmonic form from the aesthetical point of view.

The area of using the sign Í2/Ê2

(or Õ2/Q2) is wide. It is aspirate Êh or Qh, and uvular

voiceless spirant (Qh = rigid Õ), and voiceless

upper-pharyngeal spirant (hh) in Arabic. (An example of using of the

signs of Interbet for this row of sounds in the Arabic language: Í2 –

unvoiced upper-pharyngeal spirant, the sign ? – for voiced sound, Í –

lower-pharyngeal unvoiced spirant, and Õ – uvular voiceless sound, ' – guttural occlusion (laryngeal

plosive sound). For making narrower the zone of the application of the sign Í2 (=Õ2/Ê2/Q2)

the signs for velar aspirate were created — as double, mirror K (=Kh)

and uvular (Õ rounded below) – see pictures of variants. But then they were rejected

because first letter is cumbersome and second one is not clearly distinctive.

The area of Í2 is wide enough, but these sounds are close. Their difference is used

rarely and only in remote languages, for example north-Caucasian, where we can

use additionally convenient sign Õ with a cedilla as velar

voiceless spirant, in distinction of uvular. (First one is sounded softer and

that’s why a cedilla as the symbol of softness is well taken here). Õ

with a cedilla also if necessary could be used as dorsal fricative, voiceless

pair to Yot (Ich laut). The sign Q in some languages can be used as clicked

velar or even as the affricate kp.

Sonants and semi-vowels:

W -

J M - N - N2 - L - R - R2

Between sonants, the presence of two semi-vowels W and

J is doubtless (narrow labial semi-vowel is excessive from the phonematic point

of view, it has no phonematic opposition to the correspondent vowel – Ue

(U with Umlaut), but if necessary it could be denoted by letter W with trema).

The sign W can rarely play part of V2, where there is the phonematic difference

between one-labial and two-labial consonant V.

Between nasal sonants, the sign for N2 = Ng

appeared, this sound is widespread in the world. Besides, in some languages,

where there is no such sound, but there is the second N (more hard or surd,

then the main), this sign can denote it also.

The presence of one liquid and two vibrants is

explained by the fact, that the difference between velar and point L almost

nowhere plays the phonematic role (in Polish velar L is now substituted by

sound W). Where such difference exists, double LL could denote velar L. That is

why one sign for liquid is enough (though the existence of the pair to L could

give the opportunity to use it in some languages as unvoiced L or affricate tL/dL).

As for R2, this sign is necessary in some languages

where week and strong R differ, or for the aspirate Rh, or for the sound like

as Czech Rz. The presence of this sign for week R also will take part of

indicator to eritization of the sound (for example, the English and Chinese R

at the end of syllable). Existing of the convenient sign for this purpose also

influenced the choice of this sign.

During selection of the set of phonemes an idea arose

to mark out with a special signs frequent dorsal Nj è Lj,

but for these purposes there wern’t found enough perfect signs. It was decided

that the combinations of L and N with Yot could denote them. Besides, in some

languages it’s possible to depict them through corresponding letters with a

cedilla (in the east-European, where the signs with a cedilla are convenient

for denoting dorsal for S, Z, Ts, Dz). The presence of some

diacritics in Interbet is not possible to escape, especially for vowel (see

below).

Vowels:

I - Ue - U2 - U

E - Oe - E2

- Î

(E2) - A - A2/Î2

Ue and Oe here denote

front labial (U è O with Umlaut). The same signs can depict soft Russian –‘u –

and –‘o – after palatalized consonants,

as these sounds are close in this position. (One can find this idea of

depicting of the Russian vowels after palatalized consonants in the works of

the alphabet reformers of the beginning of the 20th century

L.Morohovets and Korvin-Veletsky). In the languages, where vowels with Umlaut

can stay as after unpalatalized, also after palatilized consonants

(Finno-Urgean), one of the pairs (more rare) can be denoted by diacritics. For

example, soft Ue and Oe – by the sign trema (colon) or an

inverted circumflex (haczek) above them, in contrast to hard ones (or on the

opposite: hard sounds with ^, and soft ones without). Also it’s possible in

French to write more rare closed Oe with trema, and the main opened Oe

remains plain (or closed vowel can be indicated by a double letter because it’s

always long, in contrast to opened short Îå).

As for A after palatalized consonants, its

depiction through Ae (=E2) is problematic enough, because this sign is

drawn to the position of the hard E, and not soft A, that’s why for eastern

Slavic languages A with a cedilla after palatalized consonants is suggested

(see variants). In Ukrainian E with a cedilla can denote the soft ‘e’ after

consonants, and plain E — the hard ‘e’.

Besides the main set of vowels, there are two signs

for the mixed row of vowels. They have a more wide application area: E2 can

denote the neutral vowel of the middling row (“shwa”) and also A with Umlaut

(in Germanic languages, languages of Ural family and others) — i.e. this vowel

is more opened or more back, than plain E, medium between E and A.

Among the variants there is a letter (overturned round E) for one more sign of

the A-E area, because it could be useful in many languages. But we could not

find a perfect sign for it, that’s why one can use signs E and A with a

cedilla, when necessary.

The sign A2/O2 takes part of the more back A or the

opened O or the unstressed sound of the back row, the medium between O and A

(opened O in French and many other languages, where two O’s

differ, also transcriptional letter in the form of ^ for the second A

in English or neutral U, named “yer” in Bulgarian

language).

The sign U2 is used first of all for the vowel of the

middling row (like as wide I or unround U) in Slavic, Turk or

languages of Indo-China, and for the similar sounds of the middling row in the

other languages.

CHANGES IN THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET

As the new alphabet assigns to some letters meanings

not existing in the Roman script, on the base of which the International

Phonetic Transcription was created, in the table of sounds some changes arose.

(The necessity to retain this table for the needs of linguists is obvious.)

First of all substitutes concerning sibilants, their

own original signs are assigned to them, there is also a new sign for G. It

would be good to correct the signs for interdental, making them closer to D2

and T2, and to make changes in the lines of velar and guttural. The author in

the previous article (“International practical alphabet – Interbeto". Leningrad, 1988 /25/)

suggested a new considerably extended table of IPA, but it’s not

represented here, because of the difficulty to transmit it to the simple

computer script, accessible for everybody).

(In manuscript variant of the article considerable

more quantity of the new signs is suggested than in the given set. That’s why

people, interested in these signs, can write the author, for the demonstration

of these signs or of the new, considerably enriched table of the IPA).

DIACRITICS

Even with an extensive alphabet, it’s not possible to

completely escape additional signs for letters, in order to denote modification

of sounds, not very frequent but nevertheless existing in different languages.

Even the universal IPA hasn’t avoided diacritics. The variety of vowels are the

biggest, not all of their tints have their own sounds, that is why using of

diacritics are necessary, for example, for the transcription of the long or

nasal vowel. Acute (or double letter) is used for long and tilde for nasal

letters. Also it’s possible to use the transcriptional sign of briefness for

short nasal, in distinct to long nasals (with tilde ~) in Hindu languages. For

labialized consonants one can use the transcriptional letter “^” or composition

with W or neutral À2 (similar to ^). The palatalization of a consonant can be marked by a

circumflex or the Czech “haczek” (overturned ^) above it, or by the combination

with J, or by the apostrophe. The point under a consonant can define cacuminal,

retroflex, emphatic (here a double letter can be used) or other modifications

of consonants, which differ in the concrete language.

Also a set of signs with a cedilla remains. In

Interbet these letters even have their own names, different from the main by

adding –s on the end (from the word “cedilla”): for example, A “alfa” with a

cedilla has the name “alfas”. E with a cedilla is used when lack of the set of

letters for the sound, close to E. Consonants with a cedilla are used

for blade S, Z, and palatalized sounds from Ts and Dz.

Modification of L and N with a cedilla for dorsal is possible: in such a way it

will be more convenient to overturn sign N as Russian I, for the cedilla

attached to it nicely.

The denoting of tones also requests diacritics, which

are used in transcriptions systematically enough. We can add that it would be

useful for some languages to include additional signs for meaningful categories

(for example, for Japanese, where many words sound identically. Hieroglyphic

writing differentiated them, but when using phonemic writing the difference

disappears, and now it’s suggested to introduce codes of figures to denote main

categories of meaning. Such little figures in the upper corner of the word

would help to specify the meaning of the word when necessary).

However using the words with diacritics has a

technical difficulty, from the point of view of keyboard and printing. That’s

why it’s necessary to have a substitution of a letter with a diacritic by a

combination of letters: as it’s done, for example, in the European languages,

where the vowel with Umlaut can be substituted by a combination of the main

vowel and ‘e’. It’s important that such substitutions are coordinated and

systematic. In the other cases diacritics can be omitted or substituted by the

apostrophe as a common symbol for all the diacritics (i.e. the symbol pointed

to some sound change of a letter).

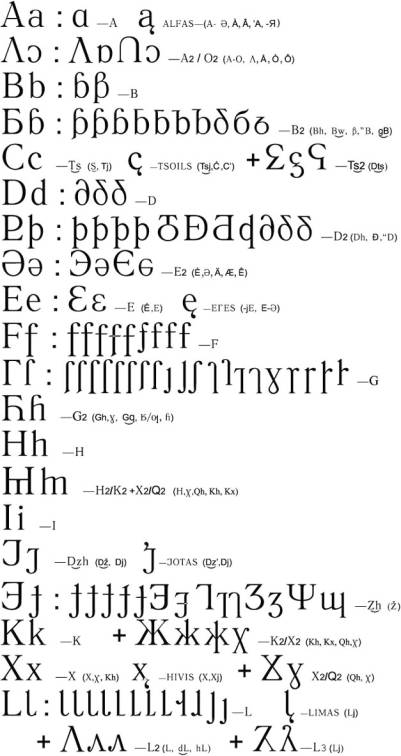

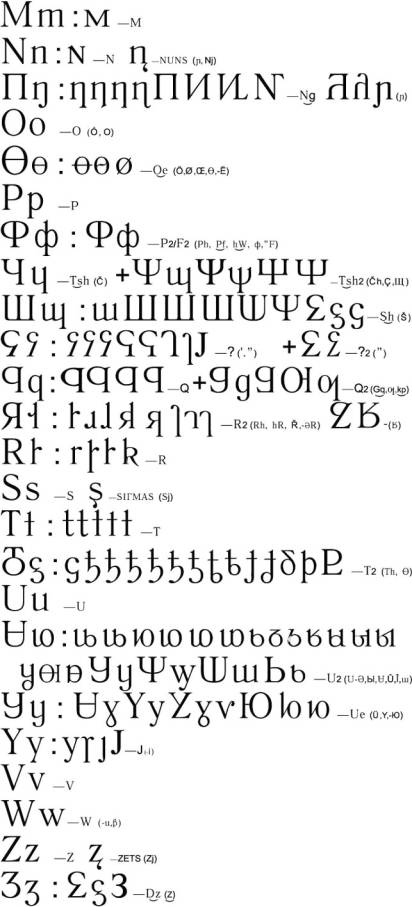

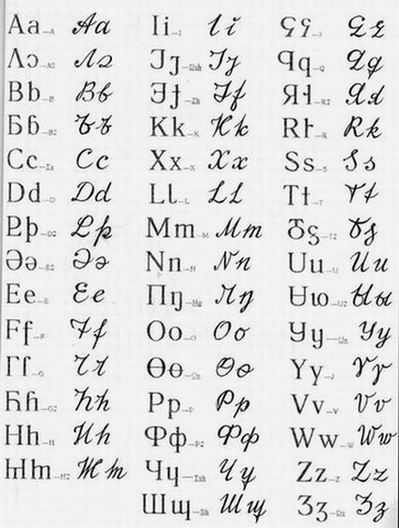

The picture of the

letters for the INTERBET is given below, with the international transcription

of the meaning of letters. After it the signs for letters with their origin are

described. A special chapter and a table are devoted to the names of letters

(see below).

PPOJECT of the

INTERNATIONAL PHONEMATIC ALPHABET

”INTERBET”

About the last changing of some signs in the alphabet

see

NEW VARIANT of the

INTERBET with the last corrections

GRAPHIC DESCRIPTION OF THE LETTERS OF INTERBET

AND THEIR ORIGIN

(The letters of

Interbet for simplicity of

understanding of their linguistic meaning

are itemized here by the symbols of the ordinary Latin letters, the

letters with the additional number 2, and underlined combinations of letters

denoting one complicated sound.)

A — historically this sign, with little changes came to Latin script

through the Greek from the first phonetic Phoenician alphabet, in which it

originates from Egyptian hieroglyph “the bow’s head”, that is Aleph (one can

recognize a bow in this letter just now, if inverted).

And in Interbet there is no problem about this letter,

only its lowercase form is changed a little to make it more clear-cut. Among the variants for the lowercase letter a more simplified one, close

to the manuscript form, is suggested. But it was rejected because this form of

A is not distinctive in a text, mixing with O.

The sign A with a cedilla can be used in a different

meaning, as additional to A (for example, for Russian as A after palatalized

consonants).

A2/O2 — the sign for the capital letter is taken from IPA (this is a

simplified variant of A, which had been used in ancient Rome in the script

named Rustic). Among the variants there is one rounded at the upper side

of the letter like as overturned U,

similar to Omega: this variant was considered if using letter ^ (big form of

circumflex) for velar L2, but then it was decided to be refused, because it is

not quite necessary and not very convenient to write.

The lowercase letter is the sign from IPA for the

opened O; this sign has been used in the Latin alphabets for the African

languages. It reminds us of the capital letter (big form of ^ in

the lateral position) and it is convenient in writing. But as a capital letter,

it’s not harmonious; in this case it mixes with the sign for Dzh and Ts

(=C).

B — historically this letter originates from the Phoenician sign Beth, represented by a picture

of a “house” on floorplan. In Interbet the sign for the capital letter

came from the Latin alphabet with no change, and small letter is

changed. It was created in order to make it similar to the capital letter,

because when having a new letter for B2, ordinary lowercase letter from Â,

‘b’ is similar to B2. Besides, the traditional lowercase b, which tends to mix with

d, therefore complicates learning. And it was decided that for the lowercase

form of B the up-rounded letter would be better. (In such a variant this letter

is used in Latin alphabet for Zulu language, and the capital letter with the

other lowercase one is used in Latin alphabet in Tibet.) But the author has

some doubt about this letter because of the not enough strict style of these

lowercase letters (and in the table below another variants are given).

B2 — for that sign the Cyrillic form of B is used, which has its

prototype in the Samaritan alphabet, directly originated from the Phoenician

script. There was a problem to find the best sign for the lowercase letter;

one can see different versions of it among the variants. If using the lowercase

for the B, then for lowercase Â2 the variants remain (from which the first was

chosen – the sign ‘b’ with the upper

horizontal serif).

C (Ts) — historically the sign “C” is the round

form of Greek Gamma, but in Latin script it had voiceless and voiced pronounciaton

(k and g). Later in Latin alphabet the modified sign for Ñ — “G” was introduced

for the voiced sound, and C had not-palatalized phonation K, and palatalized

phonation K’=TS before the vowel of the front row. In linguistic and

late Latin scripts this letter keeps meaning of the palatal whistling affricate

TS in all positions. (For the similar sound in Phoenician script there

was a letter tSadhe, a form which Cyrillic Ts and Tsh

originated.)

Now the sign Ñ for the sound Ts is quite a traditional

linguistic designation. But one can’t consider it as an ideal one, because this

affricate is not often met in world languages. So the use of this convenient

sign is very restricted. This sign is very successfully used in the Cyrillic

alphabet for the very frequent sound “s”. But when trying to use it in this

sence (or as “sh” as it was suggested in some projects at the beginning of the

20th century), a problem arises with the designation for a sound

“ts”. Only Z is associated with this sound, then for the sound “z” we must take

the letter S, so the whole system deviates strongly from the tradition of the

Latin alphabet. This deviation causes question, though it would be right from

the point of view of strengthening of the connection between the sound and its

image. More so, that in Interbet we have a more wide sign for the sibilant

“sh”, the form of C looked more harmonious, than S, as a whistling pair to it.

Also among the variants one can find the sign for Ts2

(aspirated or strengthened "Ts"). One can deal without this

sign, change it by the convenient combination CS or TÑ.

The sign C with a cedilla indicates dorsal unvoiced affricate or obstruent

sound. (As for its place in the alphabet, the letter Ts can stay after

S, having linguistic and graphic connection with it (as the pair Z and Dz).

But the last sequence is too unordinary. It creates a monotone line of sounds

B-B2- D-D2, which isn’t convenient to remember, that’s why the habitual order

of the sounds was kept.)

D — historically this Roman and Greek letters originates from

Phoenician sign Daleth (“door”, alike to this letter even now). Here a traditional variant of the sign is adopted,

though the small letter in its development deviated from the capital

one. But it’s difficult to find for it a convenient symbol more close to D (for

example, like as mirror writing of the figure 6), that’s why we has kept the

existing variant.

D2 — the author created the sign for this letter on the base of the Island rune for ‘thorn’. But this rune doesn’t adjust well to the Latin alphabet, that’s why it was modernized and received another (voiced) meaning. Voiced meaning for this sign is explained by the fact that this sign is more close to D, than to T (spirant for the last is made from T). The rune itself originates from Latin D /7/. One more proof – the inverted sign for D2 is like a sign, which is used for this meaning in Latin script for Tibet languages (here it generated from the modernized lowercase d, with a small horizontal line above). There was even an idea to use this Tibetan sign, but it strictly reflects a mirror B2, that is not good for two different sounds. A mirror similarity of the signs would be mixed in study. For the better differentiation of this lowercase letter from the small for P, the variant with the upper horizontal serif was selected.

Å2 — the sign for this sound is taken from the

table IPA, also it is used in some Cyrillic and Latin alphabets (in Turkish, African

and Tibetan). In respect to the classic construction of the uppercase letter,

the shape of the Russian capital letter as a mirror and rounded would be

better, but this sign is too close to the sign, used in Interbet for Zh,

that’s why it was rejected.

The form of the sign Å2 explains its

position in the alphabet before the main sign E. Behind the main E it would

disrupt the whole graphic movement in the sequence of the letters of the

alphabet. Another consideration is that the sign Å2 denotes more opened

sound, and the more closed naturally follows it.

E — historically this sign originated from Phoenician consonant letter

He (“bar, frame”) the Greeks began to use, as vowel Epsilon. Here this sign is used traditionally,

though among the variants there is a lowercase letter like the Greek one, and

one more sign for Å3 (like the Ukrainian je-‘e), the small letter for this is “e” or

the inverted variant of it. This sign could be an enlargement of the base of

the main vowel, but later it was decided to substitute it by the sign E with a

cedilla, because of the possibility of its mixing with the sign for Å2.

F — historically this sign came to the Latin alphabet from

western-Greek script, where it sounded as W (and had a name “digamma”), and originated

from the Phoenician sign Waw (“nail”). The Greek Y psilon originated

from another modification of the same sign.

Now

it’s a traditional sign for the Latin alphabet, though

graphically it doesn’t reflect enough the properties of the sound. To a certain

extent the small rounded shape associates with it, especially in cursive

writing, when the main vertical line (stanchion) reminds us of the sign of

integral (as a Gothic sign). So the lowercase letter has a form with a long

stanchion and a serif below. From the point of view of associaton of a sign and

a sound, the Greek letter phi fits better for this sound. But in

Interbet this sound is used for the letter with a close meaning: for bilabial

spirant or aspirate. In this meaning in some languages it’s better to use phi

and not F: for example, in Japanese, where this sound is bilabial, as well

as in the Latin alphabet for Japanese W (and not V) is used for the parallel

voiced sound.

G — for this sound Greek Gamma was elected, which generates

directly from the Phoenician symbol, unlike the Latin sign (that arose from the

adaptation of C). This Greek sign extremely well associates with the sound

itself. Historically this Greek

sign originates from Phoenician Giml, that meant a picture

of the corner (or a hump), or as

it’s translated more often “a camel”.

This Greek sign was

already used in the Latin alphabets for some eastern and African languages (as

fricative G or X=hh). Here arose a problem of its similarity to

the traditional small letter ‘r’ — that, after all, isn’t very convenient in

writing, because the longitude of the stanchion is not defined. That’s why it

was decided to change the lowercase letter for R, and for the lowercase G

several versions were suggested. We selected a variant according a natural form

sequence of letters of Interbet. Its form is the middle one between the

lowercases for F and for G2.

But during manuscript writing this sign doesn’t

strictly fix on line, that’s why there are variants with a long stanchion

and with a serif (sharp edge) below, like as for the lowercase F. Other

versions are also possible, but it’s important for this sign to have obvious

difference from the small letters for ‘f’ and ‘r’. The problem must be decided

integrally.

G2 — this sign comes from the Gothic form of H, included in the table of

IPA, this graphical sign also coincided with the similar letter for the sound

of this area in Cyrillic alphabets for Abkhase and Yakut languages, which

generates from the Greek gamma. (Also this sign, similar to the sign for the

capital, was used in some projects, extending the Roman alphabet, though as

sound Th, – after I.Pitman,

C.Luthy and Schleyer).

Í — historically this

sign originates from the Phoenician

letter Heth (“fence, stairs”). Here

the meaning of the sign is traditional for Latin script.

Í2/Ê2 — the author created the sign on the base of the main H in the same

manner of duplication as W was generated from V. Also, one of the sounds,

embraced by this sign, in the Latin script for Arabic languages is indicated by

double HH-hh. This sign is connected graphically with a modification of the

sign H (with a crossed mid-line), used in the Latin alphabet for Caucasian

languages. (The similar letter was in Karian alphabet for the sound “kh”).

I — historically this sign originated from the simplified Greek Phoenician

sign Yodh (“arm”). Now this is

a traditional sign for the vowel I, here it’s liberated from mixing with the

lowercase L (=l), which is changed in Interbet. Nevertheless its similarity with

the figure 1 remains, and this is not good — however in this case the letter

associates very well with the narrow-mouthed sound (tensive, strained like as

string). That’s why here the recommendation to write the figure 1 more

distinctly (with a definite hook) would be natural.

Dzh — this sign in Interbet originates from the Gothic form of J. Latin

J is a new letter in the alphabet, historically it comes from the letter I.

This modified letter appeared only during the Middle Ages in order to differ

the vowel and semi-vowel pronounciation of I. In many languages this sign

obtained different spirant pronounciation (j,

h, kh, zh, dzh, dz’, dj), but now the

most colloquial is the English pronounciation of Dzh, that’s why it has

such a meaning in Interbet. But the form of this sign here has, unlike J in the

late Latin script, a more complete view.

The similar form was already used in Latin alphabets

for Caucasian languages, but in another meaning (tsw or dj).

Zh — here this sign also comes

from one of the Gothic forms of J (with a horizontal cross-bar) and it reminds

us of the sign from the table IPA, for the voiced dorsal obstruent consonant.

This sign also has something in common with the sign of Interbet for Sh

in the lateral position. The sign for Zh is more complicated, than the

sign for Dzh, as the last reflects a phoneme, much more common in world

languages. The variant of the letter Zh generated from the sign Z in

Interbet is necessary for a sibilant affricate (dz) and is more

psychographic (i.e. harmonious in respect to coincidence of shape and sound) in

this meaning. The Russian letter for Zh as the double mirror K is too

bulky for the style of Interbet and is difficult to write, though

psychographically associates with this sound.

K — historically this sign originates from the Phoenician sign Kaph (“hand”, and maybe from Egyptian hieroglyph “sprouts”). Primarily in Latin script there was not such a letter, but it came from

the Greek alphabet long ago, in Antiquity for transcription of Greek words with

K before front vowels, as Latin C

(=k) before them transformed into the sound Ts.

In Interbet this sign is

traditional, psychographically it’s one of the

best signs. Only one correction in the manuscript writing of the lowercase letter

is made: it must not be like R, i.e. small k will be like the Russian small

letter (stanchion + c), but with a long stanchion.

X — this letter was probably invented by Greek, as the modification of

K, with a similar phonation — then X is pronounced as aspirate Kh, later

it had a meaning of spirant (x), though in traditional Latin script it has the phonation “ks”, but the linguists don’t use it in this quality.

In

Interbet the sign is linguistically

traditional, i.e. its phonemic meaning comes from Greek origin, as in the IPA.

Its location is connected with the previous sign K, from which an inscription

of the sign X in Greek was likely originated. In the Greek alphabet it had

fallen at the end of the alphabet as an innovation of that time. In Interbet

the position of this sign after K is stylistically and phonetically consequent.

If at the end of the alphabet it breaks the sequence of the historic and

graphic development of the signs from Y to V and W.

L — this form of the letter of the western-Greek origination arose from the Phoenician sign Lamedh (“rope, whip”). In Interbet the

capital letter is traditional, and the lowercase is changed in order to differ

more distinctly from the capital I, and to resemble the form of a capital letter. In the lower bend of the

lowercase letter there is a horizontal line with a serif.

Also a variant reminding a manuscript form was

considered, with a round bend and a vertical serif, that makes a more fixed

writing of this letter by a flourish (see the list of variants for the

lowercase letter).

M — historically this is a Phoenician sign Mem

(“water”, depicted by crests of waves). Here the letter is traditional, though for the lowercase letter a

variant arose to copy the uppercase one, because a small ‘m’ can be mixed with

the combination ‘ni’. But the author refused from this idea for the sake of the

style unity.

N — historically this is a Phoenician sign Nun (“water serpent”, which was depicted by more

curvilinear lines). The main

decision for this letter is traditional, though it was a variant to change

small n with the reduction of the capital one (as for m). This was

justified in the view of the similarity of one of the variant for the sign Ng,

considered before, with a small ‘n’. But because of selection of the another

sign for Ng, it was decided to keep the traditional variant “N-n”

without changing.

Among the variants there are signs suggested for dorsal nasal Nj. However it’s not so necessary to include unperfected signs. The variant of N with a cedilla is quite proper for the purpose, but for the sake of convenience of juncture with a cedilla it’s turned mirror-like, as the Russian I (=È).

N2 — It is mirror N with lower horizontal line, similar to the Russian letter

for joined with inverted Greek Gamma, which psychographically associates well with the sound NG. Though among the

variants there are other modifications, but in respect to convenience and

distinction they aren’t quite perfect. It was difficult to select among the

variants the sign for the lowercase letter: which would associate well with the

capital letter. Though straight letter ‘n’ with a long second stanchion is more

close to the shape of the capital one, we decided to elect the traditional sign

for this sound from the IPA. It’s already used in Latin alphabets for African

and Tibetan languages as a regular lowercase letter, though for the capital one

there is no regular form.

O — historically it is a Phoenician sign

‘Ayn (“eye”), which the Greeks began to use as vowel O. Here the meaning

of the sign is traditional.

(Apropos, for distinguishing the letter O from the figure zero, it’s convenient to use a horizontal line above the figure 0: like an upper hook of a figure 1, but more long. This is more distinctive variant, than in use now, when one crosses zero by an oblique line. It makes 0 alike to the figure 8, that can cause serious mistakes.)

Îå (the sound O with Umlaut) —

this sign, originated form O, with a horisontal cross-bar, is used in Cyrillic

alphabet, in Latin alphabets for African and Tibetan languages, and in IPA too.

In the Latin alphabet for the Danish language a diagonal crossbar is used, that

in respect of readability is justified, but aesthetically such a variant is more

questionable. For the lowercase letter it was decided to withdraw the edges of

the horizontal cross-bar of the contour of a circle -o- in order to distinguish

it better from ‘e’ and ‘e2’.

P — this is a Latin form of the writing of the Phoenician sign Pe (‘mouth”), more round and closed, than the Greek one. In Interbet this

letter is used in a traditional way.

Ð2/F2 — this sign was invented by the Greeks by

turning the letter Theta/Thita sideways, that also has aspirate meaning and

originates from the Phoenician

sign Theth (“tied up

bale of wares”).

This sign of Interbet

generates from the Greek alphabet. The shape of the uppercase letter is changed

(the circle is raised up) to make it close to the sign P.

In the lowercase letter a long upper stanchion ends on the same upper level as

the other letters with similar heads. The sign is already used in the Latin

alphabet for Tibetan languages (Lisu). And in the Latin alphabet for Caucasian

languages for an aspirate Ph, Greek form of the plain P was used, mixing with

the lowercase letter for N.

Tsh — is taken from the Cyrillic alphabet. It’s a modification of the

other Cyrillic letter Tsy, that originated from the Samaritan writing of

the Phoenician letter “Tzade”. In Phoenician this letter was sounded as acute S,

and the meaning of its name is “hook”. Another version is that this Cyrillic

sign Cherv’ generated from the ancient Greek letter Qoppa, that

disappeared from the Classic Greek alphabet.

In the meaning of Tsh this sign is used in the Latin alphabets for Tibetan and

Caucasian languages. (In the Latin alphabet for the Syrian-Circassian language

this sign is used for the sound X=hh.) In Interbet the lowercase letter

was changed in order to adopt it to the style of the Latin alphabet. The

location of the letter is explained by the fact, that in alphabets, previous to

the Latin one, the letters with the similar meaning (tSadhe in the

Phoenician alphabet and Sampi in the Greek one), were located at this site.

Sh — the pattern of this

letter is ancient enough; it was in Hebraic and Coptic alphabets, and here it

is taken from the Cyrillic alphabet and modified to make it close to the Latin

alphabet. Historically this is the Phoenician sign Shin (“teeth,

hills”), from which Greek Sigma originates. Though in Greek there was one more

letter, similar to Sh in

Interbet, that is Sampi (from the Phoenician

letter Samekh “skeleton of a fish, prop”).

Today in the

Latin alphabet this sign is used for Tibetan languages (however more likely for

the vowel of the middling row (like as wide I or unround U), than for Sh).

In Interbet the lowercase for this letter is chosen with a long lower stanchion

(similar to the Coptic one), it was done in order not to mix it with ‘m’ when

the script is small. Also this sign establishes the systematic parallel of

changing the inscription from Tsh

to Sh and from Dzh to Zh.

The location of the letter at this site is not

habitual, but it’s explained by the graphic and phonetic sequence of letters,

and by the analogy with the site of Zh behind Dzh (see before).

If considering the other versions for this letter, the

most interesting is the sign, created by the author from the capital Greek

Sigma and adapted to the style of Latin script (where the letters are more

round, than in the Greek one). This sign is good because of proximity to S and

economy of space, but is quite difficult in writing (unlike the usual Greek

Sigma, which is discordent with the style of Latin script. Isaac Pitman /8/ and

others tried to use it in this meaning, and now it is used in the Latin script

for the African languages (with a lowercase letter from IPA, similar to the

sign of integral). But in respect of psychographic resemblance, a wide double

sign for this bifocal sound would be the best.

? — this sign is represented here with a

question-mark, because it originated from it. It is included in the alphabet as

the sign, necessary for many eastern languages. Its form is connected with

transcriptional signs from the IPA, derivated from the question mark for the

sounds of the same area, — and they are close to the Arabic signs for similar

phonemes. This sign reminds us of Japhetic signs for Caucasian languages, used

in 1920-1940 in the Soviet Latin scripts. Also a similar sign is used in the

Latin alphabets for Tibetan and African

(Ojibwe) languages.

The position of the letter in the Interbet is

connected with its phonetic and graphic closeness with the next Q (the question

mark originates from the first letter of the word “Question” /6/). This sign

has the same location in the Tibetan alphabets.

Q — historically this is Phoenician sign Qoph (“a face, a back of the

head or a monkey”). As distinct from Latin Qu, in Interbet the shape of the

sign is changed to make it more classic, reflecting its Greek prototype (“Qoppa”).

However this form copies the sign Ð as a mirror makes

difficulties for learning. But, first of all, this sign is quite rare, and

secondly the capital letter’s arc is considerably larger, than in Ð. It

is especially evident when seeing the variants of the sign, suggested in the

table. For the lowercase letter it’s supposed to sharpen additionally the lower

stanchion by an oblique serif, as it is made usually in manuscript writing.

Also among the variants in the table the sign for voiced uvular consonant was

suggested (as it was mentioned above in the description of the phoneme set of

Interbet).

R2 — the sign for this letter is a mirror form of the main sign, and of

the Cyrillic letter ‘Ya’created from the modification of I+A. Here it was

adopted analogically with the sign of IPA for a modification of R. The

lowercase letter is made analogically with the small from the main R in

Interbet. The location of the additional R before the main letter is connected

with the principle of intensification, because R2 is a more faint variant of

the sound R. Also it follows graphically better from the previous sign to the

next, and the sound of the faint R is close enough to the uvular Q. This sign

is used in Latin script for Tibetan languages.

R — historically this is a Phoenician sign Resh (“a head”). In Latin

script, in contrast to the Greek one, this letter acquired a prop under the

circle that also wasn’t in the original Phoenician sign.

In Interbet the capital letter is traditional, with

some marked difference with the previous letter. The stand under the circle of

the first one has the view of a tongue, and the straight R has a stand with a

rigid serif. For the lowercase letter, as we have said in the description of

the sign for G, here such a variant of writing was found, which reminds of the

Gothic lowercase K. It is well associated with the capital R, not mixing with

the capital for G.

S — this Latin letter arose from the small Greek letters Sigma and Stigma,

originated from the Phoenician

letter Shin (see above). In

Interbet this sign is traditional, if used in the habitual meaning, but in some

cases it is different (see description of Ts=Ñ).

Among the variants there is the sign with a cedilla for the dorsal sibilant

consonant.

T — historically it was a Phoenician sign Taw (“sign, cross”,

with the crossed horizontal bar). Here the capital letter is

traditional, and it is natural, as this sign psychographically is perfect. The

lowercase letter is changed a little to the austerity of the new Greek-Latin

style: it is without a lower bend, for the sake of more clear distinction from

the lowercase L. The height of the upper stanchion is kept a little lower than

the main row of the upper stanchions (in letters b, d, k and others). But it’s

the same height, that Zh, F and I have; it‘s done for the better

distinction of the lowercase Ò from the lowercase R and R2.

T2 — the author created this sign, influenced by the letter, made for this

purpose in Latin alphabets for Turkic languages in 1920th in USSR

(NTA), and by the Greek “theta”. The similar letter is in

Devanagari (=cerebral Th); it was in the ancient Georgian script — but in the

meaning of D ("don"). That’s why an idea arose to use it as D2, and

on the contrary D2 for T2: as the sign, similar to D2, in the ancient Georgian

script reminds of the letter “tar”, that means T. But similarity of the shapes

of T2 and T had decisive importance in the final choice.

We had been seeking the small letter to this sign for a long time; and the variants show it. We had chosen the most similar letter to S, which is phonetically the most close to this interdental spirant.

U — the form of this letter arose in Latin script (possibly under the

influence of the small letter from Greek Ypsilon) only in the Middle Ages,

before this the letter V took vowel and consonant roles. In Interbet it’s a

traditional sign.

U2 — there was a long search for this letter. Finally one of the small

signs of the IPA was taken and adopted to the style of the capital letters of

Latin script. But for the lowercase, the prototype form IPA didn’t fit because

of its horisontal line, which made it looked like marked (or crossed out).

Lowercase manuscript forms of Russian letters (yery) and (yu)

helped to find the decision, having offered

several signs.

It was a variant to use this sign for the sound Ue,

where crossing of the letter is connected with its more narrow pronunciation